The foyer of the Overnight, a long, broad corridor that terminated

in a pair of elevators and stairwells, was a medley of faded and

mismatched patterns. The wallpaper featured a hexagonal motif in

pale yellow, white and green; the patterns of the carpet, tan brown

and beige, had been rendered indistinct over time. It conveyed an

atmosphere which was becoming familiar to Mark in Intermundia: a

sense of a past never quite lived in but only dimly and ruefully

recalled; a past that lived in the periphery of childhood memory, and

was glimpsed occasionally in old magazines and paperback books; the sadness of an impoverished,

unsophisticated era whose diminished horizons were embodied in its

dreams of leisure and escape.

The reception, located in the centre of the foyer, was studded with

brown vinyl. To either side of the counter there was postcard rack,

and in the centre a visitor's book and rounded silver service bell.

Behind the counter, a tall middle-aged man stood stock still and a

woman was seated, smoking a cigarette and reading a paperback novel.

Neither showed the slightest awareness of his arrival. Standing at

the far side of the counter, a small, broadly built waiter in a red

blazer grinned at Mark. The couple behind the counter conveyed a

subtle atmosphere of discontent and simmering violence which Mark

found difficult to rationalize, but which was palpable enough to make

him reluctant to approach them. The waiter's body language suggested

a worker standing at a safe distance from a piece of machinery which

experience had taught him to regard as capricious and combustable.

To postpone checking in, Mark examined a display panel on the wall

inside the door. A banner at the top of the panel read HAPPY DAY,

FELLOW FROLICKER! REMEMBERING SHELDRAKE'S SUMMER CAMPS.

Sheldrake's, he gathered, was a chain of seaside holiday resorts

which specialized in cheerful family entertainment on a modest

budget, and its ambience was conveyed in a series of black and white

photographs, fliers and assorted paraphanalia. One large photograph

depicted a phalanx of Sheldrake's staff advancing towards the camera

on a beach. Arms interlinked, they grinned broadly and indulged in

such gambolling and capers as the tight formation allowed. With the

exception of a couple at the centre, each wore the same red blazer as

the waiter, which Mark now noted was emblazed with a heraldic S on

the breast pocket. Looking closely at the image, he noted with a

start the three figures at the counter among the frolickers, to the

left of the central couple. They looked so unabashedly happy – the

man and woman gazing at one another like a newly married couple, the

young waiter participating unselfishly in their joy - that the image

formed a stark contrast to their present incarnation, with its pall

of unspoken resentment and dark, seething energy.

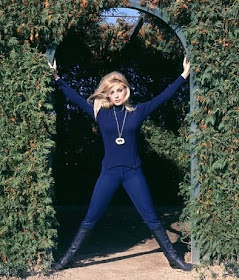

The couple in the centre of the group was an elderly business man in

a top hat and suit – Mark took this to be Sheldrake himself – and

a beautiful, statuesque blonde. Sheldrake was in his sixties, and

everything about him was round and squat. His plump, small face was

tanned and pock-mocked, and beneath a thin grey moustache his teeth

flashed in a rodent-like smirk. The blonde woman wore a sparkling sequinned jacket, tuxedo top and black tights which amply demonstrated

the smooth, supple grace of her legs. Small and indistinct as it

was, Mark became mesmerised by the image of the woman, by the

overweening perfection of her figure, the gleam of her lipstick and

the cold, insuperable distance of her smile. It stirred his first

full recollection of lust in Intermundia, perhaps because the image

appeared irretrievable in time. Another thought occurred as he stared

at the photograph: was there an ocean in Intermundia? With

that thought, he heard the swell and ebb of the sea, the timeless

respiration of the earth, the call of gulls across the sibilance of

wind and water, and the image of the woman became larger in his mind,

frozen still but always on the verge of motion and renewed vitality,

hair poised to dance in the breeze.

Started

from this brief reverie, Mark scanned some of the other images on the

display. In a poster, a disgruntled child sits weeping on his

hunches, head in hand. The unhappy boy is accosted by a group of

merry children and a large anthropomorphic white rabbit.

CHEER UP OR CLEAR OUT! the poster says. A photograph depicts a

comedian on stage, a rotund man in a chequered blazer and bow-tie,

curly brylcreemed hair and moustache, an expression both jolly and

set-upon. Teddy Bilk, the photo reads, Something Olde,

Something New, Something Borrowed and Something BLUE! Another

photo shows a figure suited up as the Sheldrake Bunny ambling down a

deserted lane between rows of chalets. Behind him, an indistinct

figure peers around the corner of one of the chalets. Alarmingly, it

appears to be a second Sheldrake Bunny, this one pitch black in

colour.

The longer he gazed at the display, Mark found that it produced

unnerving auditory effects which he could only account for as a freak

of his own imaginative suggestibility. Looking at the beach photo,

he heard the ocean. At Teddy Bilk, he heard laughter, clanking of

glasses, a ghostly intimation of Teddy's own voice, almost smelt

perspiration and perfume, sawdust and seaweed, the dulled charge of a

drunken tryst. At the picture of the Sheldrake Bunny, he heard a

terrifying sound like a machine that bore into the synapses and

caused perception to brake into waves of static. It seemed that he,

who could remember nothing of his own life, had a peculiar

susceptibility to fugitive memories that belonged only to objects and

images. He wandered away in the direction of the reception desk.

The scene there had scarcely changed since he entered the Overnight.

The woman had long fair hair, parted in the middle and flecked here

and there with grey strands. She had large blue eyes that seemed

turned inward and focused on her own thoughts, in way that made the

novel almost a prop. Her expression was patient if a little

condescending. Her skin was deeply tanned, and she wore her make-up

in the excessive fashion of an attractive woman over-compensating the

loss of her prime. She wore a light, figure-hugging summer dress

that depicted a peacock fanning its plumage against a dark blue

backdrop. She smoked her cigarette through an opera length holder.

The novel she read was called PHYSICIAN, a purportedly frank

exploration of the life-style of a cynical, ambitious and sexually

voracious young doctor.

The man, whom Mark assumed to be the manager Digsby, maintained his

peculiar pose of nervous immobility. He had wispy, thinning brown

hair combed to the side, tiny brown eyes under a pinched brow,

clean-shaven pale skin and a crookedness about the mouth that

suggested the cumulative effects of depression and cynicism.

Overall, his features evoked a foraging creature peering reluctantly

out of its den in the daylight, starving but fearful of enemies. He

wore a cream white shirt rolled up at the sleeves and a green paisley

cravat. His trousers, a peculiarly dispiriting shade of brown, were

at least a size to large for him at the waist, an exigency he had

countered by crudely extending the perforations on his belt with a

knife.

Digsby's eyes were fixed blankly on Mark, and his mouth frozen in a

toothy and joyless smile. The woman regarded Mark with a warm

expression before returning her attention to PHYSICIAN. The waiter

tilted his head towards the desk, nudging Mark to initiate the exchange.

'Excuse me,' he said finally.

'Yes?' Digsby barked.

'My name is Mark Smith.'

Digsby looked at him quizzically: 'Is it?'

'I – I have a reservation, I believe.'

'Really? Where?'

The woman glared at Digsby: 'Alan!'

'Well, here of course.'

Digsby leaned forward, sniffing the air around Mark and glancing

suspiciously in the direction of the revolving door.

'Do you have a tart waiting out there for the all-clear? Some

little check-out girl who couldn't keep her knickers up in a home for

the geriatrics?'

Mark gaped at the peculiarly belligerent hotelier. The woman

attempted to placate him:

'You're very welcome to the Intermundia Overnight. My name is

Janice. Don't mind my husband Alan – he eat something that didn't

agree with him when he was a toddler and hasn't really been himself

since. Probably his mother's milk. Did you just arrive today? You

must be very tired. Would you like us to do you up a nice

ploughman's or a corned beef?'

'We're not doing anybody a nice ploughman's – he's not some kind

of labourer, fresh from the fields and God's honest toil! He's

coming in at all hours, stinking of a brewery! He probably has a

tart out there, waiting for the all-clear.' Janice scowled. 'Alan,

for God's sake, he's a visitor, they never have tarts. They might as

well be monks, for all the interest they have.' She turned to Mark.

'I'll get you your key, love, what was the name again?'

'Mark Smith.'

Janice

turned to reach for the key but Didsby barred her, and faced Mark

with an expression of unpersuasive regret.

'No checking in after midnight, I'm afraid.'

Janice cast her eyes to heaven. 'Not this again.'

'Where am I supposed to go?'

'Well, it's unfortunate, but didn't you see the sign?' He pointed

upward to a sign over the counter that read: STRICTLY NO check-ins

after midnight by ORDER OF MANAGEMENT.

Janice addressed the

waiter, who had shrugged and smirked at Mark throughout the exchange.

'Freddie, didn't I tell you to take down that stupid sign?'

'I did take it down, love, then 'e told me to put it back up. Then

you told me to take it down, then 'e told me to put it back up again.

I'm not gonna be up and down like a bleedin jack in the box because

the left 'and don't know what the right is doing round 'ere. I don't

even like 'eights at the best of times.'

'Alan, just give him his key. How could he have seen the bloody

sign until he'd already walked in the door? No point showing him the

sign now, he's already here.'

'I know he's here! Where else would he be? But we need rules!'

The continued to bicker, their faces edging closer together,

Digsby's eyes becoming pinpricks of febrile hatred. Freddie winked

at Mark. In a sudden motion, dazzlingly brisk and graceful, he leapt

in behind Digbsy and Janice, snatched the key and resumed his

position at Mark's side. 'Let's go', he said, smiling like a clever

cocker spaniel. They walked in the direction of the stairwell.

Looking back, Mark noted that the hotelier and his wife had already

resumed their original stances, she reading her novel and he gazing

into the far distance with his rigid and unhappy grin.

'Would you prefer to take the elevator or the stairs, sir?' Freddie

asked.

'Well, which would you recommend?'

'Normally, sir, I'd recommend the stairs, because the elevator 'as

certain moods and quirks that are best avoided. Only, I've been up

and down the stairs so many times today, I'm afraid I'm likely to get

the bellicose veins, like me old dad. Me old dad used to say “Don't

send me up dem stairs again, love – you won't like me when I'm

bellicose - ”'

'Well, how about the elevator then?'

'An excellent choice, me old mucker! I can see that we will be

quite simpatico, as the French say.'

As soon as they entered the elevator, and the door shut behind them,

Freddie leaned in close and began to speak to Mark in a low,

conspiratorial tone.

'Old Digsby and Janice don't mean badly, sir, but there are a lot of

problems there, if you catch my meaning.'

'Really?'

'Yes sir. I don't think I would be speaking out of turn if I were

to say that their problems, the problems of Old Digsby and Janice,

are of a conjugal, or, how should I put it, a sexual

nature...'

Mark, unsure how to respond at this point, simply nodded.

'You see, the problem is that

whenever Janice reaches out to Old Digsby in the bedroom for 'em to

to do his duty, to tune up the old piano, so to speak, he gets his

war anxiety. Poor Digsby gets his war anxiety, and he leaps up and

jumps in under the bed, cowering, sir, as though the bleedin 'un were

about to burst in with their jerry guns blazing! 'E couldn't satisfy

a query in that frame of mind, I can assure you. I feel sorry for

Janice. She's still an attractive women, only just a tip-toe this

side of her prime. And Old Didsby can't get it up without 'earin his

drill sargent blow his whistle!'

The

surface facing them was a large, grimy mirror, and those at the sides

were papered with a puzzling heraldic pattern of scowling lions and

griffins. The air was close, and with the exception of a low humming

noise, there was little indication that the elevator was moving at

all. Mark studied Freddie in the mirror. His thick black hair

covered his ears and much of his brow like a helmet. He had small,

well-made features, large brown eyes and brows so perfectly rounded

that they looked like horizontal parentheses.

It was difficult to determine his age as his features were boyish

but his expression appeared perennially divested of all of life's

illusions and vanities. He was the type of person who might either

startle you with a display of sentimental loyalty, or casually lift

the wallet from your mortal remains. A thought occurred to Mark as

he studied him.

'Was there a war in Intermundia?'

'Was there a war? Only the bleedin Great One.'

'Was it long ago? Did you serve in it?'

'Nah, not me, sir, it was before my time. When I was a kid, I used

to listen to the War every Sunday on the radio. It was exciting for

a child, know what I mean? The 'un advancing this way, our boys

advancing that, airplane skirmishes, bombs, secret codes...it all

seems like an adventure when you're a nipper. But one day, I'm glued

to the War on the radio as usual, and me old grandad is sitting at

the table 'aving his bovril and reading the paper, when they start

listing out all the places where last night's bombs fell. All of a

sudden my ears prick up 'cause they say the name of our street, and

the very number of our bleedin building! I gets such a shock I leap

up, put me arms around the old geezer, and say: “Grandad, grandad

we're as dead as bleedin kippers!” And 'e gets a fit of laughing

and coughing as nearly does 'im in, and then he sits me down and

says: “The War ended years ago, you pillock! They just keep

playing it on the radio because it's cheaper than a variety show or a

disc jockey. Keeps people 'appy, too, son, cause people was 'appier

in the War. Gave em something to fink about and do with their time!”

So I didn't see none of the War, only what I heard on the radio.

After the Great War, sir, they 'ad what was called a Cold War, but

that wasn't really a War at all, more like two groups of lads in a

pub, looking across at each other aggro like and whispering amongst

themelves, but never actually striking a single blow. Everybody was

in a tizzy back then about Comrade infiltration. They way they 'ad

it in the news-reels, any bleedin person you meet could be a Comrade

in disguise. So I ordered a COMRADE DETECTOR KIT from the back page

of one of me comics, all excited about 'ow I was gonna smoke out

every single Comi rat on the street. But all it was was this

picture, sir, that showed some irate chap with a beard shaking his

fists, and a magnifying glass and some invisible ink. So that was as

close as I ever came to active duty. And the Cold War ended, sir,

and there ain't been nothing much as 'appened since. The planes come

and go, you people come and go, same thing every bleedin' day. I

sometimes think about what me grandad said that day, about people

being 'appier during the War cause they 'ad something to do with

their time. We was happier, sir, all of us 'ere, back when we was at

Sheldrake's. They were better times.'

'What happened? Why did you leave?'

Freddie's face clouded over, as though trying to retrieve an

indistinct memory.

'Well, I don't know, sir, fings change, I suppose. Sheldrake's

wasn't quite the draw it used to be. I remember we used to have bus loads of families, but towards the end it was only dribs and

drabs. We was trippin' over ourselves with nuffing to do. Then the sightings started, sir.'

'Sightings?'

'Sightings of the Black Bunny, sir. The thing was, we 'ad a mascot,

which was a great big jolly white rabbit, what was called, for lack

of imagination more than anything else, the Sheldrake Bunny. It was

old Digsby, if you can believe it, in a bunny suit, which Danny

Crenshaw 'ad made em do out of spite. The look on his face when that

mask came off was priceless – all sweaty, comb-over 'alf way across

the channel, blind, murderous rage in his eyes – and Crenshaw and

Teddy Bilk rolling around laughing! Anyway, people started to see a

kind of sinister twin to the jolly white rabbit lurking around the

chalets and in back of the pavilions. Identical, sir, except pure

pitch black from 'ead to foot, and also jolly, albeit in a weird and

frightening manner. All nonsense, sir, if you ask me, like moving

statues and flying spanners. Power of suggestion – mind playing

tricks on itself.'

'Anyway, then Sheldrake 'imself disappeared off the face of the

mundia. You see, to be a successful man in this world, you 'ave to

crack a few eggs, know what I mean? And old Sheldrake had cracked

more than his fair share to get where 'e was, and somebody, sir,

didn't like the flavour of the omelette. So Sheldrake was 'oled up

in his bunghole, some right dodgy sorts was sniffing round the

campsite for his blood, half the bleedin' chalets was empty, and

there was more and more sightings of the Black Bunny. And that was

the last summer we 'ad at Sheldrake's. Now, Teddy always says that

Sheldrake will come back one of these fine days, and re-open the

camp, and everything will be just like it was. But I dunno, sir, I

think that's just wishful thinking, if you was to ask me. Just

wishful thinking is all.'

A

lull fell over the conversation, and Freddie's expression became

quiescent. His eyelids

flickered and his head began to droop downward. Mark became aware

again of the low hum of the elevator, and the feeling of being

completely stationary. Struggling with a peculiar apprehension of

being rude or impolitic, he decided to broach the subject with the

dozing waiter.

'Freddie, doesn't it seem to you as though we've been in this

elevator for rather a long time?'

'Well, yes, sir, but I did warn you that the elevator has certain

peculiar quirks, didn't I? It works like normal most of the time,

but every so often....well, nobody really understands these elevator

shafts, being entirely honest with you sir. There are certain things

about this entire building, the truth be told, which are very

perplexing. A feeling one gets, from time to time, like a lot of

things went on in this hotel before we all arrived, and left, how

shall I say it, a kind of residue in the place, like the remnants of

an old cup of tea, sir, that won't be scrubbed from the bottom of the

cup.'

Freddie's eyes assumed a sober look, and his voice lowered:

'Teddy Bilk told me that one morning 'e was getting the elevator

from the top floor. And when the door opened, a figure burst out in

great haste. 'E was all dishevelled and dirty and looked like he'd

been sleeping in a gutter somewhere. Well, Teddy was a little taken

aback, and he makes a beeline into the elevator instead of

confronting 'em. Only, when the door is closing, the dishevelled

chap looks back, and Teddy nearly 'as a bleeding heart attack,

because it's himself that's looking back at him! His identical twin,

if you can believe it. Like looking at myself in a filthy mirror,

Teddy says. Anyway, the door closes, and poor Teddy is in a right

panic – he feels like he's lost every single one of his marbles. A

minute later, the door opens and Teddy steps out into the foyer –

except it ain't the bleeding foyer of the Overnight. It was a hotel,

Teddy says, but not one he'd ever clapped eyes on before in his life.

And there was something different about

the whole scene which Teddy couldn't quite put his finger on. Just a

certain something that

was off about everything – the clothes people was wearing, the

décor of the foyer, the way people was acting.'

'So Teddy is in a right panic at

this point, and 'e

just bolts right out the door of this hotel. And fings only get

worse from there, sir. Outside, 'e finds himself in this most

peculiar place where there ain't a single terminal as far as the eye

can see. And stranger still, not a single airplane to be seen in the

sky – not one! Only a handful of those critters, what do you call

them, what have evolved to imitate the airplanes - '

'Birds?'

'That's

right, sir, birds. Anyway, it was a really peculiar place, which 'ad

everything you'd find in an airport – shops, restaurants, bars –

only not a single runway or airplane in sight. Like somebody had put

everything in, only forgetting the bleedin maison

d'être, as the French say.

Teddy was in a right pickle, cause 'e couldn't speak the lingo

either. Then it occurred to him that maybe if he went back and used

the same elevator in the hotel, it might just bring him back to the

Intermundia Overnight. But by that time, sir, he'd rambled quite a

distance from the hotel, and couldn't for the life of him find it

again.'

'So

that was the beginning of a right 'ard time for old Teddy. 'E was

there for weeks, living rough on the streets, sir. It was port city,

he said, with lots of canals. The buildings was made of stone –

tall, narrow buildings, lots of bright colours, looked like they been

all squished together. And it seemed to be a place of pleasure, sir,

if you catch my meaning. The people there was transients, only

passing through to indulge themselves. A little bit like the

Greenbelt, if you credit such tales. Teddy said there was streets

where sumptuous tarts lounged in windows, waving and winking and

showing their all their inducements to the passers by, as openly,

sir, as though they was missionaries out to convert the heathen.'

'All poor Teddy could think about was his belly. 'E had to live by

his wits – to beg, borrow and steal just to stay alive. And every

day, he wandered the streets of that strange city, looking for the

hotel, still clinging to the 'ope that the elevator might bring him

back to Intermundia. Every so often, he'd hear a familiar sound,

look up, and there it was – a single airplane, streaking across the

sky – and that made him 'omesick. It made him think that maybe

there was some connection between the two worlds – that there must

be a way back.'

'In time, he encountered other castaways who'd washed up there just

like himself. One gentleman 'ad stepped into a regular telephone box,

and when he picked up the receiver, he 'eard a fearful cackle on the

other end of the line. Soon as he stepped out again, 'e had been

transported to the city of the gaily coloured stone buildings. One,

sir, 'ad been on a pier in a disreputable seaside resort, and stepped

into a booth which purported to exhibit a certain unnatural act,

ingeniously imitated by automata. He stepped out again and – bang

– 'e was far away from home. They'd all come via different routes

– mysterious booths, elevators, stairwells, dumbwaiters, strange

side-streets and alleyways what weren't normally there – and all of

em was desperately trying to get back to the part of the city where

they'd first arrived, just like Teddy. They drew maps and pictures,

sir, what was like the obessesive scrawlings of madmen, to aid their

memories, and show to passers-by in the 'ope that they might know the

way.'

'Now this put great fear into poor Teddy's heart, 'cause of some of

them castaways was old enough to 'ave one foot on the other side of

death's door. And there they was everyday, still looking for the way

home, still believing they might find deliverance from the squalid

and dirty lives they lead, when they should long ago 'ave excepted

that life had run its course for them, and they wasn't going anywhere

except the wooden box. Teddy despaired. 'E started to doubt that

Intermundia had ever existed in the first place. The whole idea –

that 'e had a missus, a nice cosy 'ouse, a job serving bitters and

tellin' a few yarns – maybe it was just a fantasy he'd made up to

make life more bearable. Maybe everybody who'd gone the wrong

direction in this life - every tramp lying in a gutter, every villain

rotting in a prison cell, every drunk waking up to the horrors –

maybe they all fashioned a story just like his, and maybe they all

had maps and diagrams, little works of fiction what was designed to

lead them to the point where they'd gone wrong, and through the magic

portal back to the place where they was supposed to be all along.'

'Well, sir, strange as it is to tell, it was precisely at that point

– when old Teddy had abandoned all hope of return, and was just on

the verge of resolving to do himself an eradicable mischief – just

at that very moment, 'e turns a corner, and lo and behold, a thrill

of recognition, a presentiment of deja vu: he is in the vicinity

of the hotel! Heart pounding til it feels like it's coming out

his gob, he turns down a side street between a wine-bar and a

florist, passes through a square where dead leaves and old newspapers

gather at the foot of a dry fountain, and onward he goes, every sight

chiming out like a deep, resonant bell through the dormant hall of

his memory, like a man possessed, he finally finds the hotel in a

narrow street where old people sit and watch from the windows of

second story apartments, and small group of stooped children trace an

image in chalk on the pavement. And 'e dashes into the hotel and

makes a beeline for the elevator, with the manager and couple of

burly waiters chasing on his heels. 'E presses the button, jumps

inside, and the door closes just as the irate mob are about to close

in on 'em. Then he presses the button for the top floor, and waits.'

'Finally, the doors open, and 'e lungs out, nearly colliding with

somebody on the way in. 'E looks back just as the doors are closing,

and realizes, sir, that it was himself he'd nearly banged into. He

'ad arrived back in the Intermundia Overnight, if you can fathom it,

at precisely the same moment that he'd left it in the first place.'

After completing his narrative, Freddie fell silent. He glanced at

Mark, and then at his own reflection in the mirrored door.

'Do you think it's true?' Mark asked him eventually.

'Well, I don't know, sir. 'E was awful sincere and serious when he

told me, and that's not normally Teddy's way. Mind you, Teddy is the

kind of fellow who can pull your leg and make you think 'e's fixing

your tie. So who knows? But I will tell you one thing. He has

never, under any circumstance, used the elevator since. And he told me,

sir, on another occasion, that he'd brought something back from the

city of the gaily coloured stone buildings. A little trinket which

he had placed in his pocket to assure himself in the years to come

that it 'ad been a real place. But he wouldn't tell me what it was.'

A sharp bell rang out, muffled female voices announced the second,

third and top floors in a jumble, and the elevator gave a little

lurch. Mark and Freddie eyed one-another nervously as the doors

began to slide open.